In my first-year memoir class, we cover Bill Roorbach’s excellent craft book, Writing Life Stories, in a year. My favorite chapter is the one about voice. The first exercise is to write a letter to someone, a letter you won’t send. Roorbach says, “This exercise always produces the best writing of the term up to the time I assign it. . . . When we address a particular person . . . we know what’s vital and urgent. . . And all this knowing gives us a clear, confident authoritative voice.”

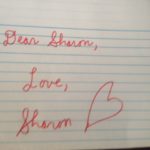

For our in-class writing assignment, I asked my class to all address the same person—their own younger self. The results were compelling. I had no idea when the fifteen-minute timer started on Thursday where I was going to go. Below are the results:

Sharon, tomorrow is your last day of seventh grade. You are thirteen. You’re not yet the mother of a thirteen year old. You to go Huff Junior High School in Lincoln Park, Michigan.

Your hair is too straight and too red and you have too many freckles. You don’t talk loudly enough, and you’re not as pretty as your sister or as smart as your brother. No, Sharon. Don’t think those thoughts. I know now they’re not true.

Not everyone has to have thick poufy hair like Charlie’s Angels. Straight will come back. Eighties style is the pits. Everything you are aspiring to look like will be laughable in a few decades.

But that’s not what I really want to tell you. I want you to know that your hair doesn’t matter. That you are smarter than you think. Your brother might have a photographic memory and be a whiz at foreign languages but you, you’re a poet. Sensitive. Perceptive. And you have emotional smarts. You don’t know yet how important this kind of intelligence will be.

You haven’t been kissed yet. You will be this summer, at your first overnight camp, one week in northern Michigan. Bible camp. The boy you’ll kiss will have even redder hair than you, if that’s possible. He’ll be tall and gangly and everyone will say what a perfect couple you are and you won’t care that the only thing you have in common is your red-hot hair.

He lives hours away from you, but you’ll exchange letters, and you’ll keep his letters under your pillow and cry a little after you read them for the four millionth time.

He’ll call one day, even though long distance is expensive, and you’ll stammer and he’ll stutter and you won’t be able to believe that after all those letters neither of you knows what to say. This exchange will come to represent for you, years later, what awkwardness is. This fumbling and stumbling will be what it means to be thirteen.

Dave. That’s his name. All your church friends will tease you about him. Your first “boyfriend,” though that seems like too important a word to call someone you never saw again. You can still feel how hard you tried to read the whole world into his letters.

My daughter is thirteen now. Tomorrow is her last day of seventh grade. When we walked the dog together, I told my daughter about Bible camp, but I didn’t mention Dave. I don’t know if my daughter has been kissed yet. Would she tell me? Did I tell my mom? Of course not.

This exercise helps teach us to be compassionate to that crazy person we used to be. Writing ourselves a letter also helps us understand how to use retrospective voice, the voice of the older (wiser?) writer, as opposed to the younger self on the page we’re writing about.

In my class we talked about the pros and cons of using present tense in memoir, and I weighed in on the con side, even though I used present tense myself in this exercise. It’s not that present tense isn’t effective, it’s that using it makes the writer’s job more difficult. Because when you insert your retrospective voice from the present, it’s got no other verb tense to use except the same one you’ve been using for the past. Which is one way I got tripped up in my exercise.

So, don’t do what I did! See how much trouble it got me in. Which is really the same thing I wish I could tell my thirteen-year-old self.